X Window System

The X Window System (commonly X or X11) is a computer software system and network protocol that provides a graphical user interface (GUI) for networked computers. It creates a hardware abstraction layer where software is written to use a generalized set of commands, allowing for device independence and reuse of programs on any computer that implements X.

X was primarily designed to implement thin clients, where many people share the processing power of a time-sharing computer, and each person uses a networked terminal that has limited capability to draw the screen and accept user input. Due to the ubiquity of support for X software on Unix, it is used on personal computers even when there is no need for time-sharing.

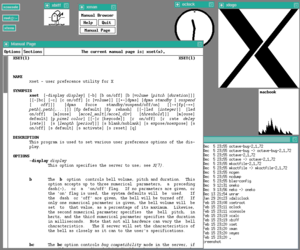

It provides windowing on computer displays and manages keyboard and pointing device control functions. In its standard distribution, it is a complete, albeit simple, display and human interface solution, which also delivers a standard toolkit and protocol stack for building graphical user interfaces on most Unix-like operating systems and OpenVMS, and has been ported to many other contemporary general purpose operating systems.

X provides the basic framework, or primitives, for building such GUI environments: drawing and moving windows on the screen and interacting with a mouse and/or keyboard. X does not mandate the user interface — individual client programs known as window managers handle this. As such, the visual styling of X-based environments varies greatly; different programs may present radically different interfaces. X is built as an additional (application) abstraction layer on top of the operating system kernel.

Unlike previous display protocols, X was specifically designed to be used over network connections rather than on an integral or attached display device. X features network transparency: the machine where an application program (the client application) runs can differ from the user's local machine (the display server), However, support for modern features like video, animation, and 3D is severely constricted by network bandwidth. In these situations other non-network display protocols such as OpenGL are commonly used to communicate with a local Graphics Processing Unit (GPU).

X originated at MIT in 1984. The current protocol version, X11, appeared in September 1987. The X.Org Foundation leads the X project, with the current reference implementation, X.Org Server, available as free and open source software under the MIT License and similar permissive licenses.[1]

X is often used in conjunction with an X session manager to implement sessions. Usually, a session is started by the X display manager. The user can however also start a session manually running the xinit or startx programs.

Contents |

Design

X uses a client–server model: an X server communicates with various client programs. The server accepts requests for graphical output (windows) and sends back user input (from keyboard, mouse, or touchscreen). The server may function as:

- an application displaying to a window of another display system

- a system program controlling the video output of a PC

- a dedicated piece of hardware.

This client–server terminology — the user's terminal being the server and the applications being the clients — often confuses new X users, because the terms appear reversed. But X takes the perspective of the application, rather than that of the end-user: X provides display and I/O services to applications, so it is a server; applications use these services, thus they are clients.

The communication protocol between server and client operates network-transparently: the client and server may run on the same machine or on different ones, possibly with different architectures and operating systems. A client and server can even communicate securely over the Internet by tunneling the connection over an encrypted network session.

An X client itself may emulate an X server by providing display services to other clients. This is known as "X nesting". Open-source clients such as Xnest and Xephyr support such X nesting.

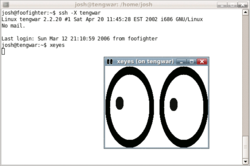

To use an X client program on a remote machine, the user does the following:

- On the local machine, open a terminal window

- use telnet or ssh to connect to the remote machine

- request local display/input service (e.g., export DISPLAY=[user's machine]:0 if not using SSH with X tunneling enabled)

The remote X client will then make a connection to the user's local X server, providing display and input to the user.

Alternatively, the local machine may run a small program that connects to the remote machine and starts the client application.

Practical examples of remote clients include:

- administering a remote machine graphically

- running a computationally intensive simulation on a remote Unix machine and displaying the results on a local Windows desktop machine

- running graphical software on several machines at once, controlled by a single display, keyboard and mouse.

Principles

In 1984, Bob Scheifler and Jim Gettys set out the early principles of X:

- Do not add new functionality unless an implementor cannot complete a real application without it.

- It is as important to decide what a system is not as to decide what it is. Do not serve all the world's needs; rather, make the system extensible so that additional needs can be met in an upwardly compatible fashion.

- The only thing worse than generalizing from one example is generalizing from no examples at all.

- If a problem is not completely understood, it is probably best to provide no solution at all.

- If you can get 90 percent of the desired effect for 10 percent of the work, use the simpler solution. (See also Worse is better.)

- Isolate complexity as much as possible.

- Provide mechanism rather than policy. In particular, place user interface policy in the clients' hands.

The first principle was modified during the design of X11 to: "Do not add new functionality unless you know of some real application that will require it."

X has largely kept to these principles. The sample implementation is developed with a view to extension and improvement of the implementation, while remaining compatible with the original 1987 protocol.

User interfaces

GNOME graphical user interface

KDE graphical user interface

Xfce graphical user interface

|

X is primarily a protocol and graphics primitives definition and it deliberately contains no specification for application user interface design, such as button, menu, or window title bar styles. Instead, application software – such as window managers, GUI widget toolkits and desktop environments, or application-specific graphical user interfaces - define and provide such details. As a result, there is no typical X interface and several desktop environments have been popular among users.

A window manager controls the placement and appearance of application windows. This may result in interfaces akin to those of Microsoft Windows or the Macintosh (examples include Metacity in GNOME, KWin in KDE, Xfwm in Xfce, or Compiz) or have radically different controls (such as a tiling window manager, like wmii or Ratpoison). Window managers range in sophistication and complexity from the bare-bones (e.g., twm, the basic window manager supplied with X, or evilwm, an extremely light window manager) to the more comprehensive desktop environments such as Enlightenment.

Many users use X with a desktop environment, which, aside from the window manager, includes various applications using a consistent user interface. GNOME, KDE and Xfce are the most popular desktop environments. The Unix standard environment is the Common Desktop Environment (CDE). The freedesktop.org initiative addresses interoperability between desktops and the components needed for a competitive X desktop.

As X is responsible for keyboard and mouse interaction with graphical desktops, certain keyboard shortcuts have become associated with X. Control-Alt-Backspace typically terminates the currently running X session, while Control-Alt in conjunction with a function key switches to the associated virtual console. However, this is an implementation detail left to the design of an X server implementation and is not universal; for example, X server implementations for Windows and Macintosh typically do not provide these keyboard shortcuts.

Implementations

The X.Org implementation serves as the canonical implementation of X. Due to liberal licensing, a number of variations, both free and open source and proprietary, have appeared. Commercial UNIX vendors have tended to take the open source implementation and adapt it for their hardware, usually customizing it and adding proprietary extensions.

Cygwin/X running rootless on Microsoft Windows XP via the command (startx -- -rootless). The screen shows X applications (xeyes, xclock, xterm) sharing the screen with native Windows applications (Date and Time, Calculator).

|

Up to 2004, XFree86 provided the most common X variant on free Unix-like systems. XFree86 started as a port of X for 386-compatible PCs and, by the end of the 1990s, had become the greatest source of technical innovation in X and the de facto standard of X development.[2] Since 2004, however, the X.Org Server, a fork of XFree86, has become predominant.

While it is common to associate X with Unix, X servers also exist natively within other graphical environments. Hewlett-Packard's OpenVMS operating system includes a version of X with CDE, known as DECwindows, as its standard desktop environment. Apple's Mac OS X v10.3 (Panther) and Mac OS X v10.4 (Tiger) include X11.app, based on XFree86 4.3 and X11R6.6, with better Mac OS X integration. On Mac OS X v10.5 (Leopard), Apple included X.org (X11R7.2 Codebase) instead of XFree86 (X11R6.8). Third-party servers under Mac OS 7, 8 and 9 included White Pine Software's eXodus and Apple's MacX.

Microsoft Windows is not shipped with support for X, but many third-party implementations exist, both free and open source software such as Cygwin/X, Xming (free up to 6.9.0.31) and WeirdX; and proprietary products such as Xmanager, Exceed, eXcursion (Hewlett-Packard), MKS X/Server, Reflection X, X-Win32, Mocha X Server[3] and Xming.

When an operating system with a native windowing system hosts X in addition, the X system can either use its own normal desktop in a separate host window or it can run rootless, meaning the X desktop is hidden and the host windowing environment manages the geometry and appearance of the hosted X windows within the host screen.

X terminals

An X terminal is a thin client that only runs an X server. This architecture became popular for building inexpensive terminal parks for many users to simultaneously use the same large computer server to execute application programs as clients of each user's X terminal. This use is very much aligned with the original intention of the MIT project.

X terminals explore the network (the local broadcast domain) using the X Display Manager Control Protocol to generate a list of available hosts that are allowed as clients. One of the client hosts should run an X display manager.

Dedicated (hardware) X terminals have become less common; a PC or modern thin client with an X server typically provides the same functionality at the same, or lower, cost.

Limitations and criticisms of X

The UNIX-HATERS Handbook (1994) devoted an entire chapter to the problems of X.[4] Why X Is Not Our Ideal Window System (1990) by Gajewska, Manasse and McCormack detailed problems in the protocol with recommendations for improvement.

User interface issues

The lack of design guidelines in X has resulted in several vastly different interfaces, and in applications that have not always worked well together. The ICCCM, a specification for client interoperability, has a reputation as being difficult to implement correctly. Further standards efforts such as Motif and CDE did not alleviate problems. This has frustrated users and programmers.[5] Graphics programmers now generally address consistency of application look and feel and communication by coding to a specific desktop environment or to a specific widget toolkit, which also avoids having to deal directly with the ICCCM.

Systems built upon the X windowing system may have accessibility issues that make utilization of a computer difficult for disabled users, including right click, double click, middle click, mouseover, and focus stealing.

Network

An X client cannot generally be detached from one server and reattached to another, as with Virtual Network Computing (VNC), though certain specific applications and toolkits are able to provide this facility.[6] Workarounds (VNC :0 viewers) also exist to make the current X-server screen available via VNC. This capability allows for the user interface (mouse, keyboard, monitor) for a running application to be switched from one location to another without stopping and restarting the application. This may be important in some applications, such as process monitoring and control.

Network traffic between an X server and remote X clients is not encrypted by default. An attacker with a packet sniffer can intercept it, making it possible to view anything displayed to or sent from the user's screen. The most common way to encrypt X traffic is to establish a Secure Shell (SSH) tunnel for communication. Lack of security is actually a feature of X, because it removes an extremely complex and high vulnerability target (secure connection manipulation) from the already large display server. Vulnerabilities in SSH can be patched independently and quickly without affecting the display server codebase.

X was developed prior to the widespread use of movies and bitmapped animation on computer displays, and handles mostly simple static graphics and text. Network-based display rendering does not have sufficient bandwidth to handle high-resolution full-screen bitmapped animation. For example a 640x480, 24 bit color, 30fps live video stream consumes 221,184,000 bits/sec uncompressed per client, or 221 megabits/sec, which far outstrips the 10 megabit Ethernet that was available when X was still new. A modern display at 1920x1200 resolution would need 1.65 gigabits/sec for full-screen live video, for each client display. These rate limits are less of an issue when the display client is used on the same computing hardware as the server, such as a personal desktop computer.

Client–server separation

X's design requires the clients and server to operate separately, and device independence and the separation of client and server incur overhead. Most of the overhead comes from network round-trip delay time between client and server (latency) rather than from the protocol itself: the best solutions to performance issues depend on efficient application design.[7] A common criticism of X is that its network features result in excessive complexity and decreased performance if only used locally.

Modern X implementations use unix domain sockets for efficient connections on the same host. Additionally shared memory (via the MIT-SHM extension) can be employed for faster client–server communication.[8] However, the programmer must still explicitly activate and use the shared memory extension. It is also necessary to provide fallback paths in order to stay compatible with older implementations, and in order to communicate with non-local X servers.

Competitors to X

For graphics, Unix-like systems use X almost universally. However, some people have attempted writing alternatives to and replacements for X. Historical alternatives include Sun's NeWS, which failed in the market, and NeXT's Display PostScript.

Mike Paquette, one of the authors of Quartz, explained why Apple did not move from Display PostScript to X, and chose instead to develop its own window server, by saying that once Apple added support for all the features it wanted to include into X11, it would not bear much resemblance to X11 nor be compatible with other servers anyway.[9]

Other attempts to address criticisms of X by replacing it completely include Berlin/Fresco and the Y Window System. These alternatives have seen negligible take-up, however, and commentators widely doubt the viability of any replacement that does not preserve backward compatibility with X.

Other competitors attempt to avoid the overhead of X by working directly with the hardware. Such projects include DirectFB. The Direct Rendering Infrastructure (DRI), which aims to provide a reliable kernel-level interface to the framebuffer, may make these efforts redundant[10].

Other ways to achieve network transparency for graphical services include:

- the SVG Terminal, a protocol to update Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) content in a browser in near-real-time

- Virtual Network Computing (VNC), a very low-level system which sends compressed bitmaps across the network; the Unix implementation includes an X server

- Citrix XenApp, an X-like product for Microsoft Windows

- Tarantella, which provides a Java client for use in web browsers

- RAWT, IBM's Java-only Remote AWT, which implements a Java "server" and simple hooks for any remote Java client.

DSPSOFT INC offers a partially proprietary windowing system called MicroXwin that is initially targeted at embedded systems. The system is not a full-fledged replacement for X but maintains binary compatibility with standard X clients while providing better performance and significantly lower memory overhead by a different architecture of design that directly implements the system as a kernel module.[11] The kernel module is proprietary while the user space libraries, libX11 (counterpart of Xlib) and libXext, are available under BSD style license.

History

Predecessors

Several bitmap display systems preceded X. From Xerox came the Alto (1973) and the Star (1981). From Apple came the Lisa (1983) and the Macintosh (1984). The Unix world had the Andrew Project (1982) and Rob Pike's Blit terminal (1982).

Carnegie-Mellon University produced a remote-access application called Alto Terminal, that displayed overlapping windows on the Xerox Alto, and made remote hosts (typically DEC VAX systems running Unix) responsible for handling window-exposure events and refreshing window contents as necessary.

X derives its name as a successor to a pre-1983 window system called W (the letter preceding X in the English alphabet). W Window System ran under the V operating system. W used a network protocol supporting terminal and graphics windows, the server maintaining display lists.

Origin and early development

The original idea of X emerged at MIT in 1984 as a collaboration between Jim Gettys (of Project Athena) and Bob Scheifler (of the MIT Laboratory for Computer Science). Scheifler needed a usable display environment for debugging the Argus system. Project Athena (a joint project between Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), MIT and IBM to provide easy access to computing resources for all students) needed a platform-independent graphics system to link together its heterogeneous multiple-vendor systems; the window system then under development in Carnegie Mellon University's Andrew Project did not make licenses available, and no alternatives existed.

The project solved this by creating a protocol that could both run local applications and call on remote resources. In mid-1983 an initial port of W to Unix ran at one-fifth of its speed under V; in May 1984, Scheifler replaced the synchronous protocol of W with an asynchronous protocol and the display lists with immediate mode graphics to make X version 1. X became the first windowing system environment to offer true hardware independence and vendor independence.

Scheifler, Gettys and Ron Newman set to work and X progressed rapidly. They released Version 6 in January 1985. DEC, then preparing to release its first Ultrix workstation, judged X the only windowing system likely to become available in time. DEC engineers ported X6 to DEC's QVSS display on MicroVAX.

In the second quarter of 1985 X acquired color support to function in the DEC VAXstation-II/GPX, forming what became version 9.

A group at Brown University ported version 9 to the IBM RT/PC, but problems with reading unaligned data on the RT forced an incompatible protocol change, leading to version 10 in late 1985. By 1986, outside organizations had started asking for X. The release of X10R2 took place in January 1986; that of X10R3 in February 1986. Although MIT had licensed X6 to some outside groups for a fee, it decided at this time to license X10R3 and future versions under what became known as the MIT License, intending to popularize X further and in return, hoping that many more applications would become available. X10R3 became the first version to achieve wide deployment, with both DEC and Hewlett-Packard releasing products based on it. Other groups ported X10 to Apollo and to Sun workstations and even to the IBM PC/AT. Demonstrations of the first commercial application for X (a mechanical computer-aided engineering system from Cognition Inc. that ran on VAXes and displayed on PCs running an X server) took place at the Autofact trade show at that time. The last version of X10, X10R4, appeared in December 1986.

Attempts were made to enable X servers as real-time collaboration devices, much as Virtual Network Computing (VNC) would later allow a desktop to be shared. One such early effort was Philip J. Gust's SharedX tool.

Although X10 offered interesting and powerful functionality, it had become obvious that the X protocol could use a more hardware-neutral redesign before it became too widely deployed, but MIT alone would not have the resources available for such a complete redesign. As it happened, DEC's Western Software Laboratory found itself between projects with an experienced team. Smokey Wallace of DEC WSL and Jim Gettys proposed that DEC WSL build X11 and make it freely available under the same terms as X9 and X10. This process started in May 1986, with the protocol finalized in August. Alpha testing of the software started in February 1987, beta-testing in May; the release of X11 finally occurred on September 15, 1987.

The X11 protocol design, led by Scheifler, was extensively discussed on open mailing lists on the nascent Internet that were bridged to USENET newsgroups. Gettys moved to California to help lead the X11 development work at WSL from DEC's Systems Research Center, where Phil Karlton and Susan Angebrandt led the X11 sample server design and implementation. X therefore represents one of the first very large-scale distributed free and open source software projects.

The MIT X Consortium and the X Consortium, Inc.

In 1987, with the success of X11 becoming apparent, MIT wished to relinquish the stewardship of X, but at a June 1987 meeting with nine vendors, the vendors told MIT that they believed in the need for a neutral party to keep X from fragmenting in the marketplace. In January 1988, the MIT X Consortium formed as a non-profit vendor group, with Scheifler as director, to direct the future development of X in a neutral atmosphere inclusive of commercial and educational interests. Jim Fulton joined in January 1988 and Keith Packard in March 1988 as senior developers, with Jim focusing on Xlib, fonts, window managers, and utilities; and Keith re-implementing the server. Donna Converse, Chris D. Peterson, and Stephen Gildea joined later that year, focusing on toolkits and widget sets, working closely with Ralph Swick of MIT Project Athena. The MIT X Consortium produced several significant revisions to X11, the first (Release 2 - X11R2) in February 1988. Jay Hersh joined the staff in January 1991 to work on the PEX and X113D functionality. He was followed soon after by Ralph Mor (who also worked on PEX) and Dave Sternlicht. In 1993, as the MIT X Consortium prepared to depart from MIT, the staff were joined by R. Gary Cutbill, Kaleb Keithley, and David Wiggins.[12]

In 1993, the X Consortium, Inc. (a non-profit corporation) formed as the successor to the MIT X Consortium. It released X11R6 on May 16, 1994. In 1995 it took on the development of the Motif toolkit and of the Common Desktop Environment for Unix systems. The X Consortium dissolved at the end of 1996, producing a final revision, X11R6.3, and a legacy of increasing commercial influence in the development.[13][14]

The Open Group

In January 1997 the X Consortium passed stewardship of X to The Open Group, a vendor group formed in early 1996 by the merger of the Open Software Foundation and X/Open.

The Open Group released X11R6.4 in early 1998. Controversially, X11R6.4 departed from the traditional liberal licensing terms, as the Open Group sought to assure funding for the development of X.[15] The new terms would have prevented its adoption by many projects (such as XFree86) and even by some commercial vendors. After XFree86 seemed poised to fork, the Open Group relicensed X11R6.4 under the traditional license in September 1998.[16] The Open Group's last release came as X11R6.4 patch 3.

X.Org and XFree86

XFree86 originated in 1992 from the X386 server for IBM PC compatibles included with X11R5 in 1991, written by Thomas Roell and Mark W. Snitily and donated to the MIT X Consortium by Snitily Graphics Consulting Services (SGCS). XFree86 evolved over time from just one port of X to the leading and most popular implementation and the de facto standard of X's development.[2]

In May 1999, the Open Group formed X.Org. X.Org supervised the release of versions X11R6.5.1 onward. X development at this time had become moribund;[17] most technical innovation since the X Consortium had dissolved had taken place in the XFree86 project.[18] In 1999, the XFree86 team joined X.Org as an honorary (non-paying) member,[19] encouraged by various hardware companies[20] interested in using XFree86 with Linux and in its status as the most popular version of X.

By 2003, while the popularity of Linux (and hence the installed base of X) surged, X.Org remained inactive,[21] and active development took place largely within XFree86. However, considerable dissent developed within XFree86. The XFree86 project suffered from a perception of a far too cathedral-like development model; developers could not get CVS commit access[22][23] and vendors had to maintain extensive patch sets.[24] In March 2003 the XFree86 organization expelled Keith Packard, who had joined XFree86 after the end of the original MIT X Consortium, with considerable ill-feeling.[25][26][27]

X.Org and XFree86 began discussing a reorganisation suited to properly nurturing the development of X.[28][29][30] Jim Gettys had been pushing strongly for an open development model since at least 2000.[31] Gettys, Packard and several others began discussing in detail the requirements for the effective governance of X with open development.

Finally, in an echo of the X11R6.4 licensing dispute, XFree86 released version 4.4 in February 2004 under a more restrictive license which many projects relying on X found unacceptable.[32] The added clause to the license was based upon the original BSD license's advertising clause, which was viewed by the Free Software Foundation and Debian as incompatible with the GNU General Public License.[33] Other groups saw it as against the spirit of the original X. Theo de Raadt of OpenBSD, for instance, threatened to fork XFree86 citing license concerns.[34] The license issue, combined with the difficulties in getting changes in, left many feeling the time was ripe for a fork.[35]

The X.Org Foundation

In early 2004 various people from X.Org and freedesktop.org formed the X.Org Foundation, and the Open Group gave it control of the x.org domain name. This marked a radical change in the governance of X. Whereas the stewards of X since 1988 (including the previous X.Org) had been vendor organizations, the Foundation was led by software developers and used community development based on the bazaar model, which relies on outside involvement. Membership was opened to individuals, with corporate membership being in the form of sponsorship. Several major corporations such as Hewlett-Packard and Sun Microsystems currently support the X.Org Foundation.

The Foundation takes an oversight role over X development: technical decisions are made on their merits by achieving rough consensus among community members. Technical decisions are not made by the board of directors; in this sense, it is strongly modelled on the technically non-interventionist GNOME Foundation. The Foundation does not employ any developers.

The Foundation released X11R6.7, the X.Org Server, in April 2004, based on XFree86 4.4RC2 with X11R6.6 changes merged. Gettys and Packard had taken the last version of XFree86 under the old license and, by making a point of an open development model and retaining GPL compatibility, brought many of the old XFree86 developers on board.[33]

X11R6.8 came out in September 2004. It added significant new features, including preliminary support for translucent windows and other sophisticated visual effects, screen magnifiers and thumbnailers, and facilities to integrate with 3D immersive display systems such as Sun's Project Looking Glass and the Croquet project. External applications called compositing window managers provide policy for the visual appearance.

On December 21, 2005,[36] X.Org released X11R6.9, the monolithic source tree for legacy users, and X11R7.0, the same source code separated into independent modules, each maintainable in separate projects.[37] The Foundation released X11R7.1 on May 22, 2006, about four months after 7.0, with considerable feature improvements.[38]

On the other side, XFree86 is still being developed at a very slow pace, and version 4.8.0 was released on 15 December 2008[39]

Future directions

The X.Org Foundation and freedesktop.org managed the main line of X development and they intend to provide more access to ubiquitous 3D hardware features. For sufficiently capable combinations of hardware and operating systems, X.Org plans to access the video hardware only via the Direct Rendering Infrastructure (DRI), using the 3D hardware. The DRI first appeared in XFree86 version 4.0 and became standard in X11R6.7 and later and this work is ongoing.[40]

Nomenclature

People in the computer trade commonly shorten the phrase "X Window System" to "X Window", "X11" (for version 11, used since 1987) or simply to "X".[41] The term "X-Windows" (in the manner of "Microsoft Windows") is not officially endorsed, though it has been in common use since early in the history of X and has been used deliberately for provocative effect, for example in the UNIX-HATERS Handbook.[42]

Release history

| Version | Release date | Most important changes |

|---|---|---|

| X1 | June 1984 | First use of the name "X"; fundamental changes distinguishing the product from W. |

| X6 | January 1985 | First version licensed to a handful of outside companies. |

| X9 | September 1985 | Color. First release under MIT License. |

| X10 | late 1985 | IBM RT/PC, AT (running DOS), and others |

| X10R2 | January 1986 | |

| X10R3 | February 1986 | First freely redistributable X release. Earlier releases required a BSD source license to cover code changes to init/getty to support login. uwm made standard window manager. |

| X10R4 | December 1986 | Last version of X10. |

| X11 | September 15, 1987 | First release of the current protocol. |

| X11R2 | February 1988 | First X Consortium release.[43] |

| X11R3 | October 25, 1988 | XDM |

| X11R4 | December 22, 1989 | XDMCP, twm brought in as standard window manager, application improvements, Shape extension, new fonts. |

| X11R5 | September 5, 1991 | PEX, Xcms (color management), font server, X386, X video extension |

| X11R6 | May 16, 1994 | ICCCM v2.0; Inter-Client Exchange; X Session Management; X Synchronization extension; X Image extension; XTEST extension; X Input; X Big Requests; XC-MISC; XFree86 changes. |

| X11R6.1 | March 14, 1996 | X Double Buffer extension; X keyboard extension; X Record extension. |

| X11R6.2 X11R6.3 (Broadway) |

December 23, 1996 | Web functionality, LBX. Last X Consortium release. X11R6.2 is the tag for a subset of X11R6.3 with the only new features over R6.1 being XPrint and the Xlib implementation of vertical writing and user-defined character support.[44] |

| X11R6.4 | March 31, 1998 | Xinerama.[45] |

| X11R6.5 | Internal X.org release; not made publicly available. | |

| X11R6.5.1 | August 20, 2000 | |

| X11R6.6 | April 4, 2001 | Bug fixes, XFree86 changes. |

| X11R6.7.0 | April 6, 2004 | First X.Org Foundation release, incorporating XFree86 4.4rc2. Full end-user distribution. Removal of XIE, PEX and libxml2.[46] |

| X11R6.8.0 | September 8, 2004 | Window translucency, XDamage, Distributed Multihead X, XFixes, Composite.XEvIE |

| X11R6.8.1 | September 17, 2004 | Security fix in libxpm. |

| X11R6.8.2 | February 10, 2005 | Bug fixes, driver updates. |

| X11R6.9 X11R7.0 |

December 21, 2005 | EXA, major source code refactoring.[47] From the same source-code base, the modular autotooled version became 7.0 and the monolithic imake version was frozen at 6.9. |

| X11R7.1 | May 22, 2006 | EXA enhancements, KDrive integrated, AIGLX, OS and platform support enhancements.[48] |

| X11R7.2 | February 15, 2007 | Removal of LBX and the built-in keyboard driver, X-ACE, XCB, autoconfig improvements, cleanups.[49] |

| X11R7.3 | September 6, 2007 | XServer 1.4, Input hotplug, output hotplug (RandR 1.2), DTrace probes, PCI domain support.[50] |

| X11R7.4 | September 23, 2008 | XServer 1.5.1, XACE, PCI-rework, EXA speed-ups, _X_EXPORT, GLX 1.4, faster startup and shutdown.[51] |

| X11R7.5 | October 26, 2009 [52] | XServer 1.7, Xi 2, XGE, E-EDID support, RandR 1.3, MPX, predictable pointer acceleration, DRI2 memory manager, SELinux security module, further removal of obsolete libraries and extensions.[53] |

Forthcoming releases

| Version | Release date | Most important planned changes |

|---|---|---|

| X11R7.6 | October 2010[54] | Xi 3 and XKB 2, possible XCB requirement[55], X Server 1.9 |

See also

- History of the graphical user interface

- X11 color names

- Xgl

- General Graphics Interface

- VirtualGL

- rio - the windowing system for Plan 9

- List of Unix programs

- DESQview/X

- Cairo (graphics)

- Y Window System

- XFree86

Notes

- ↑ "Licenses". X11 documentation. X.org. 19 December 2005. http://ftp.x.org/pub/X11R7.0/doc/html/LICENSE.html. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Announcement: Modification to the base XFree86(TM) license. 02 Feb 2004

- ↑ http://www.mochasoft.dk/freeware/x11.htm

- ↑ ""The X-Windows Disaster"". Art.net. http://www.art.net/~hopkins/Don/unix-haters/x-windows/disaster.html. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- ↑ Re: X is painful 15 Nov 1996

- ↑ SNAP Computing and the X Window System 2005 (section 4.6, the xmove program)

- ↑ An LBX Postmortem 2001-1-24

- ↑ The XFree86 documentation of the MIT-SHM extension 2009-05-14

- ↑ Why Apple didn't use X for the window system August 19, 2007

- ↑ DRI for framebuffer consoles December 15, 2009

- ↑ MicroXwin Performance on OMAP1710 Retrieved on 2009-03-24.

- ↑ Robert W. Scheifler and James Gettys: X Window System: Core and extension protocols: X version 11, releases 6 and 6.1, Digital Press 1996, ISBN 1-55558-148-X

- ↑ Financing Volunteer Free Software Projects 10 Jun 2005

- ↑ Lessons Learned about Open Source 2000

- ↑ X statement 02 Apr 1998

- ↑ X11R6.4 Sample Implementation Changes and Concerns

- ↑ Q&A: The X Factor February 04, 2002

- ↑ The Evolution of the X Server Architecture 1999

- ↑ A Call For Open Governance Of X Development 23 Mar 2003

- ↑ XFree86 joins X.Org as Honorary Member Dec 01, 1999

- ↑ Another teleconference partial edited transcript 13 Apr 2003

- ↑ Keith Packard issue 20 Mar 2003

- ↑ Cygwin/XFree86 - No longer associated with XFree86.org 27 Oct 2003

- ↑ On XFree86 development 9 Jan 2003

- ↑ Invitation for public discussion about the future of X 20 Mar 2003

- ↑ A Call For Open Governance Of X Development 21 Mar 2003

- ↑ Notes from a teleconference held 2003-3-27 03 Apr 2003

- ↑ A Call For Open Governance Of X Development 24 Mar 2003

- ↑ A Call For Open Governance Of X Development 23 Mar 2003

- ↑ Discussing issues 14 Apr 2003

- ↑ Lessons Learned about Open Source 2000

- ↑ XFree86 4.4: List of Rejecting Distributors Grows Feb 18, 2004

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Appendix A: The Cautionary Tale of XFree86 June 5, 2002

- ↑ Theo de Raadt (February 16, 2004). "openbsd-misc Mailing List: XFree86 license". MARC. Archived from the original on December 8, 2009. http://www.webcitation.org/5lsZKRQmU. Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- ↑ X Marks the Spot: Looking back at X11 Developments of Past Year Feb 25, 2004

- ↑ X11R6.9 and X11R7.0 Officially Released December 21, 2005

- ↑ Modularization Proposal 2005-03-31

- ↑ Proposed Changes for X11R7.1 2006-04-21

- ↑ XFree86 4.8.0 release

- ↑ Getting X Off The Hardware July, 2004

- ↑ X - a portable, network-transparent window system February 2005

- ↑ "The X-Windows Disaster". Art.net. http://www.art.net/~hopkins/Don/unix-haters/x-windows/disaster.html. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- ↑ The X Window System: History and Architecture 1 September 1999

- ↑ XFree86 and X11R6.3 December 1999

- ↑ The Open Group Announces Internet-Ready X Window System X11R6.4 March 31, 1998

- ↑ X.Org Foundation releases X Window System X11R6.7 April 7, 2004

- ↑ Changes Since R6.8 2005-10-21

- ↑ Release Notes for X11R7.1 22 May 2006

- ↑ The X.Org Foundation released 7.2.0 (aka X11R7.2) February 15th, 2007

- ↑ X server version 1.4 release plans. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ↑ "Foundation Releases X7.4". X.org. http://www.x.org/wiki/Releases/7.4. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- ↑ "7.5 release announcement". X.org. http://www.x.org/wiki/Other/Press/X11R75Released. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- ↑ "Wiki - 7.5 release plans". X.org. http://www.x.org/wiki/Releases/7.5. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- ↑ "X.Org 7.6 May Be Released In October 2010". Phoronix.com. 2009-10-21. http://www.phoronix.com/scan.php?page=news_item&px=NzYyNA. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- ↑ "Thinking towards 7.6 katamari, including xcb". Lists.x.org. http://lists.x.org/archives/xorg-devel/2009-October/002995.html. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

References

- Hania Gajewska, Mark S. Manasse and Joel McCormack, Why X Is Not Our Ideal Window System (PDF), Software — Practice & Experience vol 20, issue S2 (October 1990)

- Linda Mui and Eric Pearce, X Window System Volume 8: X Window System Administrator's Guide for X11 Release 4 and Release 5, 3rd edition (O'Reilly and Associates, July 1993; softcover ISBN 0-937175-83-8)

- The X-Windows Disaster (UNIX-HATERS Handbook)

- Robert W. Scheifler and James Gettys: X Window System: Core and extension protocols: X version 11, releases 6 and 6.1, Digital Press 1996, ISBN 1-55558-148-X

- The Evolution of the X Server Architecture (Keith Packard, 1999)

- The means to an X for Linux: an interview with David Dawes from XFree86.org (Matthew Arnison, CAT TV, June 1999)

- Lessons Learned about Open Source (Jim Gettys, USENIX 2000 talk on the history of X)

- On the Thesis that X is Big/Bloated/Obsolete and Should Be Replaced (Christopher B. Browne)

- Open Source Desktop Technology Road Map (Jim Gettys, 9 December 2003)

- X Marks the Spot: Looking back at X11 Developments of Past Year (Oscar Boykin, OSNews, 25 February 2004)

- Getting X Off The Hardware (Keith Packard, July 2004 Ottawa Linux Symposium talk)

- Why Apple didn't use X for the window system (Mike Paquette, Apple Computer)

- X Man Page (Retrieved on 2 February 2007)

- SNAP Computing and the X Window System (Jim Gettys, 2005)

External links

- X.Org Foundation Official website

- The X Window System: A Brief Introduction

- Window managers for X

- The State of Linux Graphics (Jon Smirl, 30 August 2005)

- Kenton Lee: Technical X Window System and Motif WWW Sites

- RFC 1198 - FYI on the X Window System

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||